The integration of machine learning into dynamic particle image analysis marks a transformative leap in the study of intricate physical phenomena.

Such data is routinely produced via ultrafast imaging in domains like fluid mechanics, combustion science, and 粒子形状測定 biomedical diagnostics capture the motion and interactions of thousands to millions of particles over time.

Legacy techniques employing human annotation or rudimentary binarization struggle with the scale, noise, and variability inherent in such data.

AI-driven methods provide a scalable solution by autonomously detecting features, categorizing particle classes, and forecasting dynamics without rule-based coding for each case.

The enormous data throughput from high-speed imaging poses serious logistical and computational hurdles.

One run may produce multiple terabytes of visual data, rendering human labeling unfeasible.

Supervised learning models, such as convolutional neural networks, can be trained on labeled examples to detect and segment individual particles in each frame.

The trained systems enable near-real-time processing, slashing turnaround times by orders of magnitude.

Architectures such as U-Net and Mask R-CNN demonstrate superior precision in segmenting fused or asymmetric particles, even with poor contrast.

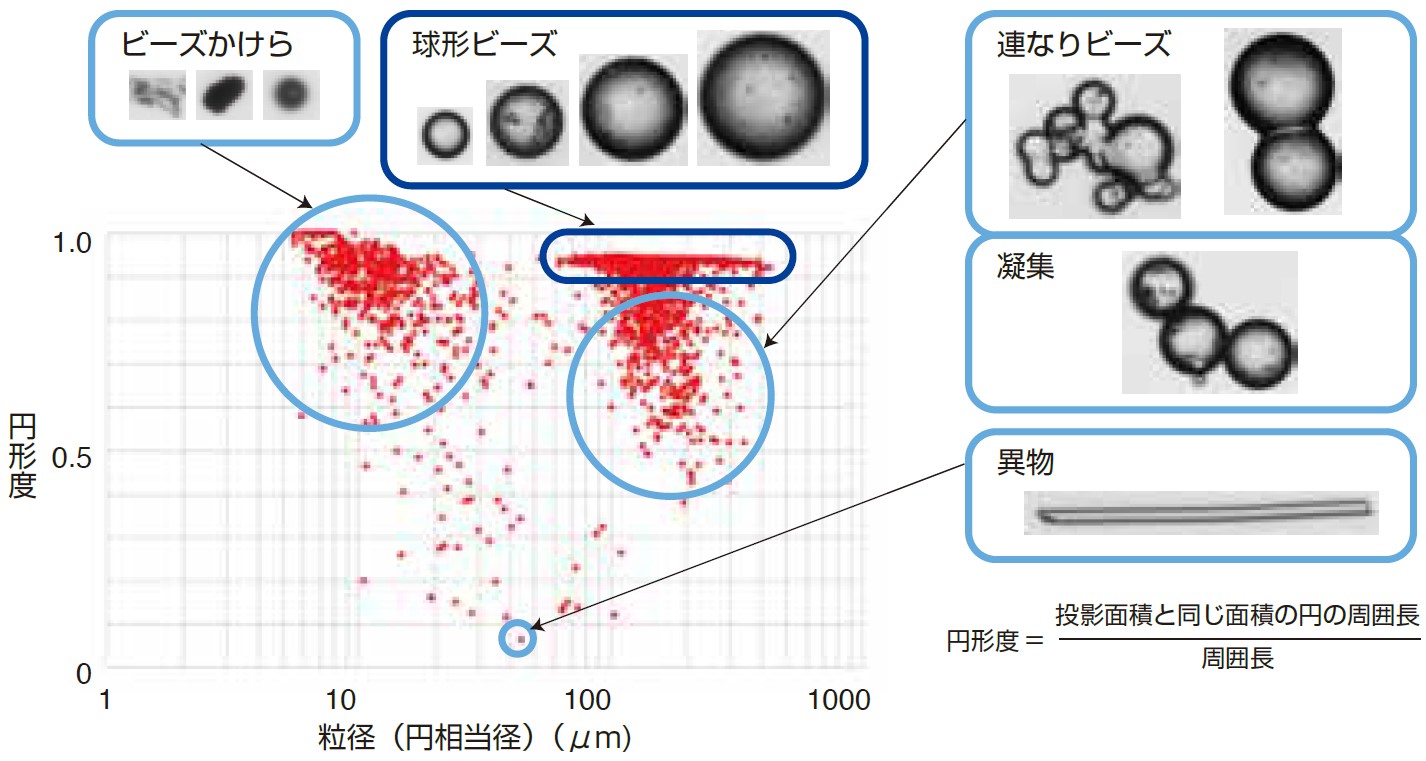

Machine learning extends beyond detection to categorize particles using features derived from their structure, movement, or optical signatures.

In medical imaging, ML can differentiate erythrocytes, thrombocytes, and artifacts in vascular flows via combined feature analysis and SVM.

In industrial settings, such as spray characterization or particulate emission monitoring, clustering algorithms like k means or DBSCAN can group particles with similar trajectories, revealing underlying flow structures or source mechanisms.

Analyzing particle evolution across frames is another area where AI delivers exceptional performance.

Recurrent neural networks, especially long short term memory networks, can model the evolution of particle motion across consecutive frames.

This allows for the prediction of future positions, identification of vortices or turbulence patterns, and detection of anomalies such as sudden accelerations or clustering events.

By embedding physical principles into neural architectures, models adhere to fundamental laws such as momentum conservation and Stokes’ drag, enhancing reliability and explainability.

The integration of unsupervised and self supervised learning methods is also gaining traction.

These methods learn robust feature embeddings without human-provided labels, making them ideal for large-scale, unlabeled datasets.

Autoencoders, for example, can compress high dimensional image data into lower dimensional latent spaces that capture essential features of particle dynamics, facilitating visualization and downstream analysis.

Despite these advances, challenges remain.

Factors like uneven illumination, optical distortions, and varying particle densities significantly affect model reliability.

Robust preprocessing pipelines, including background subtraction, contrast normalization, and data augmentation, are essential.

Additionally, model interpretability remains a concern; while deep learning models perform well, understanding why a model classified a particle in a certain way can be difficult.

Techniques such as attention maps and gradient based saliency visualization are being explored to bridge this gap.

Integrating machine learning with real-time acquisition opens the door to dynamic, responsive experimental setups.

For example, in microfluidic devices, machine learning models could dynamically adjust flow rates based on real time particle behavior, enabling adaptive experiments.

Shared computational ecosystems using cloud resources, collaborative labeling, and public repositories are expanding access.

In summary, machine learning transforms the analysis of dynamic particle image datasets from a labor intensive, rule based process into an automated, scalable, and insightful endeavor.

With advancing algorithms and growing computing power, scientists in physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering will turn to ML to reveal latent structures, test theoretical frameworks, and spark new discoveries.